History of Venetian glass

Since the time of ancient Rome to today, Venetian glass has been a major part of Venetian history and has set the destiny of people on Murano.

The Roman Empire

The history of Venetian glass started with Roman glass in the Roman Empire (1st century BC to 5th century AD). Glassblowing was a revolutionary invention already used by many glass factories throughout the Italian peninsula. Glassmaking techniques and glassware spread throughout the world. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the glass industry quickly declined.

Rialto

In the 8th century, the central part of the Venetian Republic moved to Rialto, where many churches and cathedrals were built all over the island. Many glass factories also moved to Rialto.

Booming glass industry

In 1078, the reconstruction of St. Mark’s Basilica started. Glass mosaics were installed on all the walls. According to historical documents, 29 glassworkers were fined for violating glassmaking customs and regulations. This indicates a booming glass industry.

Governmental protection and control

The 13th century saw major involvement of the government in the Venetian glass industry. It formed the Venetian Glass Guild in 1268, concluded contracts with Antioch (Syria’s largest producer of glass) to import raw glass materials, directly controlled firewood to streamline fuel management, and banned operations in summer.

Then in 1291, the Venetian government, seeking to protect the Venetian glass industry, enacted a law to require all glass makers, assistants, and their families to move to Murano island. Any escapees would be punished with death. The development of Venetian glass then centered on Murano.

The heyday of Venetian glass

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Venetian glass developed under the strong influence of Byzantine and Islamic aesthetics, especially in enameling techniques and designs. In the 15th century, it matured further with the backdrop of the Italian Renaissance.

In the latter half of the 16th century, Venetian glass reached its zenith with many groundbreaking techniques for finer and more splendid designs like diamond-point engraving, lace glass (filigrana), crystal glass, crackled glass, and marbled glass. Glassware in diverse forms for diverse functions were produced.

Hard times

In the 18th century, a new industrialism emerged in Europe when countries imposed high tariffs on imported goods to protect domestic industries. As a result, glass-producing countries suffered a drastic drop in exports and many glass factories went bankrupt. Murano was no exception.

To overcome these hard times, Murano glassmakers did whatever they could to survive by producing finer mosaics, church interiors and ornaments, and exporting to Africa and Southeast Asia. However, the dissolution of the Venetian Republic in 1797 marked the end of governmental patronage of the glass industry. Ten years later in 1806, Murano’s venerable glassmakers’ guild was forced to disband after 500 years.

The modernization of Venetian glass

While Murano’s glass industry faced stagnation, modernization kicked off a new era in the 19th century. Many museums and archives were established as new platforms for industry and education. The new museums needed vintage artifacts to be exhibited. But there were not enough of them, so Murano’s master glassmakers created replicas of ancient glassware.

This was followed by their glass mosaic techniques with colored glass inimitable by any glassmaker in any other country. They restored old church murals and created a new sector for interior design glasswork. It was a new beginning after a period of hardship.

Murano also saw many new movements. They included the construction of modern factories, the loosening of the closed system, the establishment of educational institutions for apprentices, the construction of glass museums, and the organizing of exhibitions and research societies. Through the cooperation of pioneering leaders and traditional craftsmen, Venetian glass arose from a dark period to go forward on the path to modernization.

History of Venetian glass

Since the time of ancient Rome to today, Venetian glass has been a major part of Venetian history and has set the destiny of people on Murano.

The Roman Empire

The history of Venetian glass started with Roman glass in the Roman Empire (1st century BC to 5th century AD). Glassblowing was a revolutionary invention already used by many glass factories throughout the Italian peninsula. Glassmaking techniques and glassware spread throughout the world. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the glass industry quickly declined.

Rialto

In the 8th century, the central part of the Venetian Republic moved to Rialto, where many churches and cathedrals were built all over the island. Many glass factories also moved to Rialto.

Booming glass industry

In 1078, the reconstruction of St. Mark’s Basilica started. Glass mosaics were installed on all the walls. According to historical documents, 29 glassworkers were fined for violating glassmaking customs and regulations. This indicates a booming glass industry.

Governmental protection and control

The 13th century saw major involvement of the government in the Venetian glass industry. It formed the Venetian Glass Guild in 1268, concluded contracts with Antioch (Syria’s largest producer of glass) to import raw glass materials, directly controlled firewood to streamline fuel management, and banned operations in summer.

Then in 1291, the Venetian government, seeking to protect the Venetian glass industry, enacted a law to require all glass makers, assistants, and their families to move to Murano island. Any escapees would be punished with death. The development of Venetian glass then centered on Murano.

The heyday of Venetian glass

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Venetian glass developed under the strong influence of Byzantine and Islamic aesthetics, especially in enameling techniques and designs. In the 15th century, it matured further with the backdrop of the Italian Renaissance.

In the latter half of the 16th century, Venetian glass reached its zenith with many groundbreaking techniques for finer and more splendid designs like diamond-point engraving, lace glass (filigrana), crystal glass, crackled glass, and marbled glass. Glassware in diverse forms for diverse functions were produced.

Hard times

In the 18th century, a new industrialism emerged in Europe when countries imposed high tariffs on imported goods to protect domestic industries. As a result, glass-producing countries suffered a drastic drop in exports and many glass factories went bankrupt. Murano was no exception.

To overcome these hard times, Murano glassmakers did whatever they could to survive by producing finer mosaics, church interiors and ornaments, and exporting to Africa and Southeast Asia. However, the dissolution of the Venetian Republic in 1797 marked the end of governmental patronage of the glass industry. Ten years later in 1806, Murano’s venerable glassmakers’ guild was forced to disband after 500 years.

The modernization of Venetian glass

While Murano’s glass industry faced stagnation, modernization kicked off a new era in the 19th century. Many museums and archives were established as new platforms for industry and education. The new museums needed vintage artifacts to be exhibited. But there were not enough of them, so Murano’s master glassmakers created replicas of ancient glassware.

This was followed by their glass mosaic techniques with colored glass inimitable by any glassmaker in any other country. They restored old church murals and created a new sector for interior design glasswork. It was a new beginning after a period of hardship.

Murano also saw many new movements. They included the construction of modern factories, the loosening of the closed system, the establishment of educational institutions for apprentices, the construction of glass museums, and the organizing of exhibitions and research societies. Through the cooperation of pioneering leaders and traditional craftsmen, Venetian glass arose from a dark period to go forward on the path to modernization.

技法

馬賽克玻璃(千花玻璃)

此種玻璃在公元前15世紀左右就已於美索不達米亞地區生產,並在公元前2世紀至公元1世紀的古羅馬帝國進一步盛行。而後雖一度式微,但19世紀由威尼斯玻璃工匠修復出技法。馬賽克玻璃使用各種圖案的玻璃製作,需將多層玻璃覆蓋的玻璃粒薄拉延伸,形成玻璃棒,然後水平切割而成。由於此種玻璃看起來就像玻璃容器中盛開著花朵,因此人們亦稱它為「millefiori」,也就是義大利文「一千朵花」的意思,

蕾絲玻璃

此為一種玻璃的統稱,係指結合透明玻璃與乳白色等彩色玻璃,做出以細線描繪、宛如蕾絲編織圖案的玻璃器皿。

從公元前3世紀起,義大利和亞歷山卓的玻璃器皿中均存在相同技法的作品,然而將此技術發展起來並加以完善的是16世紀中葉的威尼斯工匠玻璃工匠。

此後,精密細緻的蕾絲玻璃便成了威尼斯玻璃的代名詞。在義大利,蕾絲玻璃被稱為filigrana,又依照乳白色玻璃描繪出的花樣大致分為三類,扭紋圖案的玻璃稱作a retorti;方格圖案的玻璃稱作a reticello;平行條紋圖案的玻璃稱作a fili。

大理石花紋玻璃

將不同顏色的玻璃熔煉結合形成底部,再於表面呈現大理石、玉髓、瑪瑙等天然寶石的圖案。大理石玻璃中,有一種基底含有銀離子、光線穿透會變為紅色的玻璃被稱為 Carcedonio(義大利文的「紅玉髓」)。此種玻璃於15世紀末的威尼斯研發,並流行於16、17世紀。之後的17世紀末到18世紀,更生產出鑲有東陵石的玻璃作品,這是一種金屬及金屬化合物於玻璃內產生的結晶。

技法

馬賽克玻璃(千花玻璃)

此種玻璃在公元前15世紀左右就已於美索不達米亞地區生產,並在公元前2世紀至公元1世紀的古羅馬帝國進一步盛行。而後雖一度式微,但19世紀由威尼斯玻璃工匠修復出技法。馬賽克玻璃使用各種圖案的玻璃製作,需將多層玻璃覆蓋的玻璃粒薄拉延伸,形成玻璃棒,然後水平切割而成。由於此種玻璃看起來就像玻璃容器中盛開著花朵,因此人們亦稱它為「millefiori」,也就是義大利文「一千朵花」的意思,

蕾絲玻璃

此為一種玻璃的統稱,係指結合透明玻璃與乳白色等彩色玻璃,做出以細線描繪、宛如蕾絲編織圖案的玻璃器皿。

從公元前3世紀起,義大利和亞歷山卓的玻璃器皿中均存在相同技法的作品,然而將此技術發展起來並加以完善的是16世紀中葉的威尼斯工匠玻璃工匠。

此後,精密細緻的蕾絲玻璃便成了威尼斯玻璃的代名詞。在義大利,蕾絲玻璃被稱為filigrana,又依照乳白色玻璃描繪出的花樣大致分為三類,扭紋圖案的玻璃稱作a retorti;方格圖案的玻璃稱作a reticello;平行條紋圖案的玻璃稱作a fili。

大理石花紋玻璃

將不同顏色的玻璃熔煉結合形成底部,再於表面呈現大理石、玉髓、瑪瑙等天然寶石的圖案。大理石玻璃中,有一種基底含有銀離子、光線穿透會變為紅色的玻璃被稱為 Carcedonio(義大利文的「紅玉髓」)。此種玻璃於15世紀末的威尼斯研發,並流行於16、17世紀。之後的17世紀末到18世紀,更生產出鑲有東陵石的玻璃作品,這是一種金屬及金屬化合物於玻璃內產生的結晶。

威尼斯玻璃美術館 代表作品

威尼斯玻璃美術館 代表作品

現代玻璃美術館

走入20世紀,注入新生命的新穎現代玻璃藝術作品。

威尼斯玻璃雕刻師李維奧‧瑟古茲及美國玻璃藝術家戴爾·奇胡利的作品展。

現代玻璃美術館

走入20世紀,注入新生命的新穎現代玻璃藝術作品。

威尼斯玻璃雕刻師李維奧‧瑟古茲及美國玻璃藝術家戴爾·奇胡利的作品展。

藝術家介紹

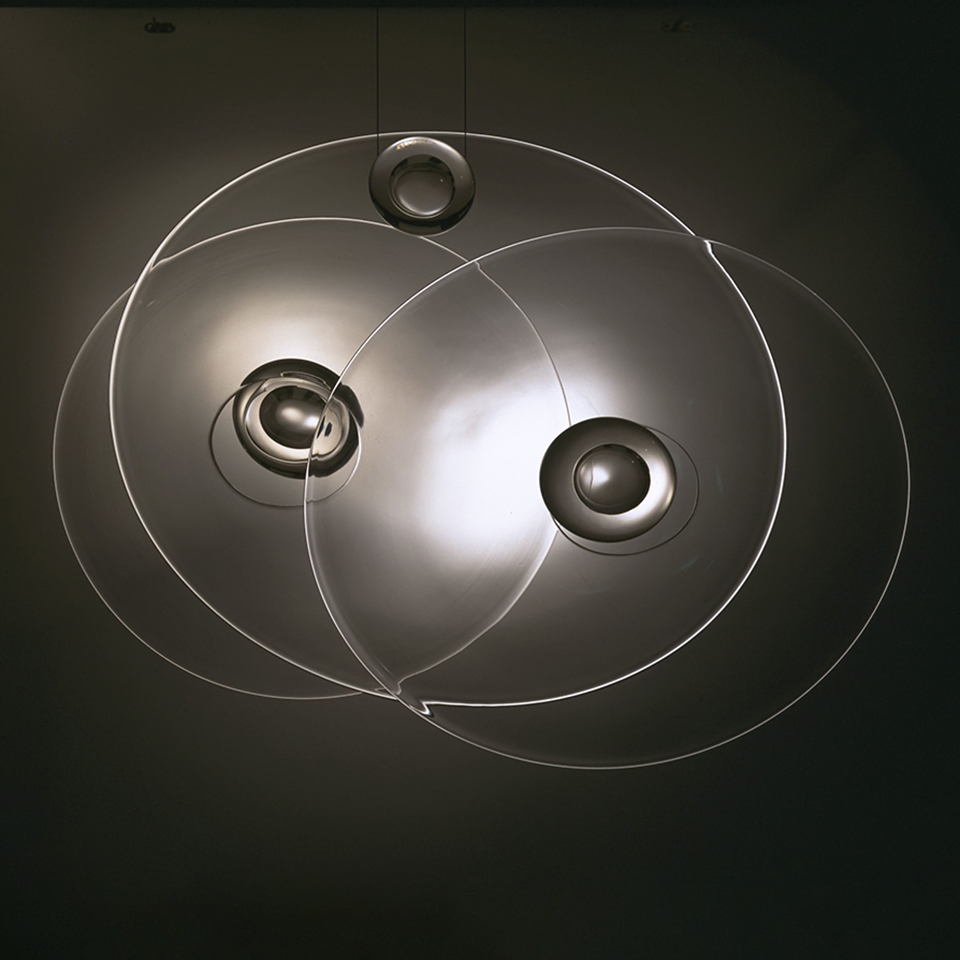

Livio Seguso

1930~

瑟古茲出生於威尼斯。自少年時期便為玻璃此一材質當中蘊含的魅力深深著迷。

他的叔叔是活躍於國際的玻璃大師阿爾弗雷德·巴比尼 (Alfred Barbini),在叔叔的指導下他學習了威尼斯玻璃美術館的傳統技術。

瑟古茲20歲便成為玻璃吹製大師,鑽研玻璃雕塑並創作融合形式、空間及光線的作品,力求將無色透明的玻璃之美提昇至極限。

1970年代末期以來,瑟古茲運用精緻的圓形和橢圓形樹立了獨特的自我風格。

又於1980年代進行新的嘗試,將自己製作的圓形玻璃切割成幾塊,重新建構出與原來形狀不同的物體。

至今仍持續將玻璃與金屬、大理石和木材等不同材料結合,創作出融合自身內在豐富詩意情懷及通透玻璃之美的作品。

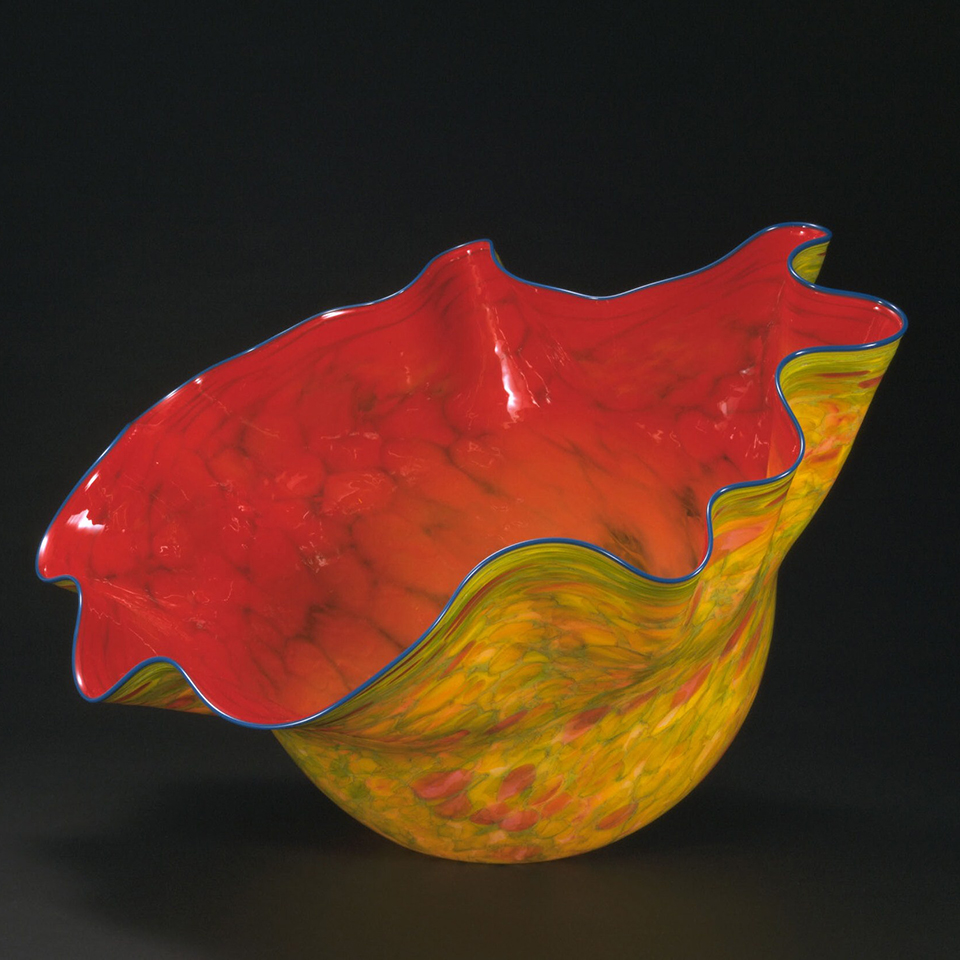

Dale Chihuly

1941~

奇胡利在華盛頓大學學習室內設計時認識了玻璃。由於對玻璃蘊藏的可能性深深著迷,奇胡利便於1965年進入威斯康辛大學就讀,並師從工作室玻璃運動的倡導者哈維·K·利特爾頓 (Harvey K. Littleton)。

1968年,奇胡利前往威尼斯的穆拉諾島留學,於維尼尼工坊深受威尼斯玻璃傳統以及團隊創作風格的影響。而後便以穆拉諾島的留學經驗為基礎,在1971年於華盛頓州與他人共同創辦玻璃教育機構「Pilchuck Glass School」,為全世界的玻璃創作者提供一個鑽研及資訊交流的場域,至今仍不斷為玻璃界做出貢獻。

奇胡利陸續發表了發揮無與倫比想像力、色彩、造形品味的《Machia斑點》(1981年~)、《Persian波斯》(1986年~)、《Venetian 威尼斯人》(1988年~)等展現豐富生命力及動感的系列作品。奇胡利曾獲得「美國人間國寶獎」(1992年)等眾多殊榮,並受邀於1996年威尼斯舉辦的「當代國際玻璃藝術家展」展出作品,2012年則於西雅圖中心開設強調庭園與玻璃相互共鳴的「奇胡利玻璃藝術花園」,積極地開展活動。

現代玻璃美術館

走入20世紀,注入新生命的新穎現代玻璃藝術作品。

威尼斯玻璃雕刻師李維奧‧瑟古茲及美國玻璃藝術家戴爾·奇胡利的作品展。

現代玻璃美術館

走入20世紀,注入新生命的新穎現代玻璃藝術作品。

威尼斯玻璃雕刻師李維奧‧瑟古茲及美國玻璃藝術家戴爾·奇胡利的作品展。

藝術家介紹

Livio Seguso

1930~

瑟古茲出生於威尼斯。自少年時期便為玻璃此一材質當中蘊含的魅力深深著迷。

他的叔叔是活躍於國際的玻璃大師阿爾弗雷德·巴比尼 (Alfred Barbini),在叔叔的指導下他學習了威尼斯玻璃美術館的傳統技術。

瑟古茲20歲便成為玻璃吹製大師,鑽研玻璃雕塑並創作融合形式、空間及光線的作品,力求將無色透明的玻璃之美提昇至極限。

1970年代末期以來,瑟古茲運用精緻的圓形和橢圓形樹立了獨特的自我風格。

又於1980年代進行新的嘗試,將自己製作的圓形玻璃切割成幾塊,重新建構出與原來形狀不同的物體。

至今仍持續將玻璃與金屬、大理石和木材等不同材料結合,創作出融合自身內在豐富詩意情懷及通透玻璃之美的作品。

Dale Chihuly

1941~

奇胡利在華盛頓大學學習室內設計時認識了玻璃。由於對玻璃蘊藏的可能性深深著迷,奇胡利便於1965年進入威斯康辛大學就讀,並師從工作室玻璃運動的倡導者哈維·K·利特爾頓 (Harvey K. Littleton)。

1968年,奇胡利前往威尼斯的穆拉諾島留學,於維尼尼工坊深受威尼斯玻璃傳統以及團隊創作風格的影響。而後便以穆拉諾島的留學經驗為基礎,在1971年於華盛頓州與他人共同創辦玻璃教育機構「Pilchuck Glass School」,為全世界的玻璃創作者提供一個鑽研及資訊交流的場域,至今仍不斷為玻璃界做出貢獻。

奇胡利陸續發表了發揮無與倫比想像力、色彩、造形品味的《Machia斑點》(1981年~)、《Persian波斯》(1986年~)、《Venetian 威尼斯人》(1988年~)等展現豐富生命力及動感的系列作品。奇胡利曾獲得「美國人間國寶獎」(1992年)等眾多殊榮,並受邀於1996年威尼斯舉辦的「當代國際玻璃藝術家展」展出作品,2012年則於西雅圖中心開設強調庭園與玻璃相互共鳴的「奇胡利玻璃藝術花園」,積極地開展活動。