The pinnacle of beauty with outstanding skill

Utmost talents for ultimate beauty. Enjoy the brilliance of fine, elegant glass to your heart’s content. The museum’s collection of about 1,000 pieces centers on the golden age of Venetian glass from the 15th to 16th centuries, ancient glass from over 2,000 years ago, ornamental glass revived by Salviati and others in the 19th century, and glass art from the 20th century. The museum exhibits about 100 highly selective glass pieces in special exhibitions held year-round.

The pinnacle of beauty with outstanding skill

Utmost talents for ultimate beauty. Enjoy the brilliance of fine, elegant glass to your heart’s content. The museum’s collection of about 1,000 pieces centers on the golden age of Venetian glass from the 15th to 16th centuries, ancient glass from over 2,000 years ago, ornamental glass revived by Salviati and others in the 19th century, and glass art from the 20th century. The museum exhibits about 100 highly selective glass pieces in special exhibitions held year-round.

The pinnacle of beauty with outstanding skill

Utmost talents for ultimate beauty. Enjoy the brilliance of fine, elegant glass to your heart’s content. The museum’s collection of about 1,000 pieces centers on the golden age of Venetian glass from the 15th to 16th centuries, ancient glass from over 2,000 years ago, ornamental glass revived by Salviati and others in the 19th century, and glass art from the 20th century. The museum exhibits about 100 highly selective glass pieces in special exhibitions held year-round.

The pinnacle of beauty with outstanding skill

Utmost talents for ultimate beauty. Enjoy the brilliance of fine, elegant glass to your heart’s content. The museum’s collection of about 1,000 pieces centers on the golden age of Venetian glass from the 15th to 16th centuries, ancient glass from over 2,000 years ago, ornamental glass revived by Salviati and others in the 19th century, and glass art from the 20th century. The museum exhibits about 100 highly selective glass pieces in special exhibitions held year-round.

History of Venetian glass

Since the time of ancient Rome to today, Venetian glass has been a major part of Venetian history and has set the destiny of people on Murano.

The Roman Empire

The history of Venetian glass started with Roman glass in the Roman Empire (1st century BC to 5th century AD). Glassblowing was a revolutionary invention already used by many glass factories throughout the Italian peninsula. Glassmaking techniques and glassware spread throughout the world. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the glass industry quickly declined.

Rialto

In the 8th century, the central part of the Venetian Republic moved to Rialto, where many churches and cathedrals were built all over the island. Many glass factories also moved to Rialto.

Booming glass industry

In 1078, the reconstruction of St. Mark’s Basilica started. Glass mosaics were installed on all the walls. According to historical documents, 29 glassworkers were fined for violating glassmaking customs and regulations. This indicates a booming glass industry.

Governmental protection and control

The 13th century saw major involvement of the government in the Venetian glass industry. It formed the Venetian Glass Guild in 1268, concluded contracts with Antioch (Syria’s largest producer of glass) to import raw glass materials, directly controlled firewood to streamline fuel management, and banned operations in summer.

Then in 1291, the Venetian government, seeking to protect the Venetian glass industry, enacted a law to require all glass makers, assistants, and their families to move to Murano island. Any escapees would be punished with death. The development of Venetian glass then centered on Murano.

The heyday of Venetian glass

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Venetian glass developed under the strong influence of Byzantine and Islamic aesthetics, especially in enameling techniques and designs. In the 15th century, it matured further with the backdrop of the Italian Renaissance.

In the latter half of the 16th century, Venetian glass reached its zenith with many groundbreaking techniques for finer and more splendid designs like diamond-point engraving, lace glass (filigrana), crystal glass, crackled glass, and marbled glass. Glassware in diverse forms for diverse functions were produced.

Hard times

In the 18th century, a new industrialism emerged in Europe when countries imposed high tariffs on imported goods to protect domestic industries. As a result, glass-producing countries suffered a drastic drop in exports and many glass factories went bankrupt. Murano was no exception.

To overcome these hard times, Murano glassmakers did whatever they could to survive by producing finer mosaics, church interiors and ornaments, and exporting to Africa and Southeast Asia. However, the dissolution of the Venetian Republic in 1797 marked the end of governmental patronage of the glass industry. Ten years later in 1806, Murano’s venerable glassmakers’ guild was forced to disband after 500 years.

The modernization of Venetian glass

While Murano’s glass industry faced stagnation, modernization kicked off a new era in the 19th century. Many museums and archives were established as new platforms for industry and education. The new museums needed vintage artifacts to be exhibited. But there were not enough of them, so Murano’s master glassmakers created replicas of ancient glassware.

This was followed by their glass mosaic techniques with colored glass inimitable by any glassmaker in any other country. They restored old church murals and created a new sector for interior design glasswork. It was a new beginning after a period of hardship.

Murano also saw many new movements. They included the construction of modern factories, the loosening of the closed system, the establishment of educational institutions for apprentices, the construction of glass museums, and the organizing of exhibitions and research societies. Through the cooperation of pioneering leaders and traditional craftsmen, Venetian glass arose from a dark period to go forward on the path to modernization.

History of Venetian glass

Since the time of ancient Rome to today, Venetian glass has been a major part of Venetian history and has set the destiny of people on Murano.

The Roman Empire

The history of Venetian glass started with Roman glass in the Roman Empire (1st century BC to 5th century AD). Glassblowing was a revolutionary invention already used by many glass factories throughout the Italian peninsula. Glassmaking techniques and glassware spread throughout the world. However, with the fall of the Roman Empire in 476, the glass industry quickly declined.

Rialto

In the 8th century, the central part of the Venetian Republic moved to Rialto, where many churches and cathedrals were built all over the island. Many glass factories also moved to Rialto.

Booming glass industry

In 1078, the reconstruction of St. Mark’s Basilica started. Glass mosaics were installed on all the walls. According to historical documents, 29 glassworkers were fined for violating glassmaking customs and regulations. This indicates a booming glass industry.

Governmental protection and control

The 13th century saw major involvement of the government in the Venetian glass industry. It formed the Venetian Glass Guild in 1268, concluded contracts with Antioch (Syria’s largest producer of glass) to import raw glass materials, directly controlled firewood to streamline fuel management, and banned operations in summer.

Then in 1291, the Venetian government, seeking to protect the Venetian glass industry, enacted a law to require all glass makers, assistants, and their families to move to Murano island. Any escapees would be punished with death. The development of Venetian glass then centered on Murano.

The heyday of Venetian glass

In the 13th and 14th centuries, Venetian glass developed under the strong influence of Byzantine and Islamic aesthetics, especially in enameling techniques and designs. In the 15th century, it matured further with the backdrop of the Italian Renaissance.

In the latter half of the 16th century, Venetian glass reached its zenith with many groundbreaking techniques for finer and more splendid designs like diamond-point engraving, lace glass (filigrana), crystal glass, crackled glass, and marbled glass. Glassware in diverse forms for diverse functions were produced.

Hard times

In the 18th century, a new industrialism emerged in Europe when countries imposed high tariffs on imported goods to protect domestic industries. As a result, glass-producing countries suffered a drastic drop in exports and many glass factories went bankrupt. Murano was no exception.

To overcome these hard times, Murano glassmakers did whatever they could to survive by producing finer mosaics, church interiors and ornaments, and exporting to Africa and Southeast Asia. However, the dissolution of the Venetian Republic in 1797 marked the end of governmental patronage of the glass industry. Ten years later in 1806, Murano’s venerable glassmakers’ guild was forced to disband after 500 years.

The modernization of Venetian glass

While Murano’s glass industry faced stagnation, modernization kicked off a new era in the 19th century. Many museums and archives were established as new platforms for industry and education. The new museums needed vintage artifacts to be exhibited. But there were not enough of them, so Murano’s master glassmakers created replicas of ancient glassware.

This was followed by their glass mosaic techniques with colored glass inimitable by any glassmaker in any other country. They restored old church murals and created a new sector for interior design glasswork. It was a new beginning after a period of hardship.

Murano also saw many new movements. They included the construction of modern factories, the loosening of the closed system, the establishment of educational institutions for apprentices, the construction of glass museums, and the organizing of exhibitions and research societies. Through the cooperation of pioneering leaders and traditional craftsmen, Venetian glass arose from a dark period to go forward on the path to modernization.

Technique

Mosaic glass (Millefiori glass)

B.C. and developed further in the Roman Empire from the 2nd century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. After a period of decline, mosaic glass was revived by Venetian glassmakers in the 19th century. Mosaic glass is made with small pieces of glass embedded with diverse patterns. The small glass pieces are made from glass canes created with multiple layers of glass to create a pattern. The cane is stretched out, then cut into small, cross-section pieces. Mosaic glass is called millefiori, meaning “thousand flowers” in Italian because they look like flowers blooming on the glass vessel.

Lace glass

created by combining transparent glass and colored glass such as milky white. Although there are examples of this technique in Italian and Alexandrian glassware from the 3rd century BC, Venetian glassmakers further developed and refined the technique in the mid-16th century. Fine and exquisite lace glass has since become synonymous with Venetian glass. In Italy, lace glass is called filigrana which is classified into three main types depending on the pattern of the milky white glass. A retorti is a twisted pattern, a reticello is a criss-cross pattern, and a fili is parallel stripes.

Marbled glass

Marbled glass is made by melting different colored glass and kneading them into a base material. The glass surface has the pattern of natural precious stones such as marble, chalcedony, or agate. Chalcedony, or calcedonio in Italian meaning “red marble,” was developed in Venice in the latter 15th century and became popular during the 16th to 17th centuries. The glass has silver ions and the glass color becomes red when light penetrates it, hence its Italian name. From the latter 17th to 18th century, aventurine glassware was also made with metal pieces or metallic particles crystallized in the glass.

Technique

Mosaic glass (Millefiori glass)

B.C. and developed further in the Roman Empire from the 2nd century B.C. to the 1st century A.D. After a period of decline, mosaic glass was revived by Venetian glassmakers in the 19th century. Mosaic glass is made with small pieces of glass embedded with diverse patterns. The small glass pieces are made from glass canes created with multiple layers of glass to create a pattern. The cane is stretched out, then cut into small, cross-section pieces. Mosaic glass is called millefiori, meaning “thousand flowers” in Italian because they look like flowers blooming on the glass vessel.

Lace glass

created by combining transparent glass and colored glass such as milky white. Although there are examples of this technique in Italian and Alexandrian glassware from the 3rd century BC, Venetian glassmakers further developed and refined the technique in the mid-16th century. Fine and exquisite lace glass has since become synonymous with Venetian glass. In Italy, lace glass is called filigrana which is classified into three main types depending on the pattern of the milky white glass. A retorti is a twisted pattern, a reticello is a criss-cross pattern, and a fili is parallel stripes.

Marbled glass

Marbled glass is made by melting different colored glass and kneading them into a base material. The glass surface has the pattern of natural precious stones such as marble, chalcedony, or agate. Chalcedony, or calcedonio in Italian meaning “red marble,” was developed in Venice in the latter 15th century and became popular during the 16th to 17th centuries. The glass has silver ions and the glass color becomes red when light penetrates it, hence its Italian name. From the latter 17th to 18th century, aventurine glassware was also made with metal pieces or metallic particles crystallized in the glass.

Featured pieces in the Venetian Glass Museum

Featured pieces in the Venetian Glass Museum

Modern Glass Museum

A novel contemporary glass art work that has been breathed new life into the 20th century.

Exhibiting works by Venetian glass sculptor Livio Seguso and American glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Discover the endless possibilities of glass.

Modern Glass Museum

A novel contemporary glass art work that has been breathed new life into the 20th century.

Exhibiting works by Venetian glass sculptor Livio Seguso and American glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Discover the endless possibilities of glass.

Artist introduction

Livio Seguso

1930~

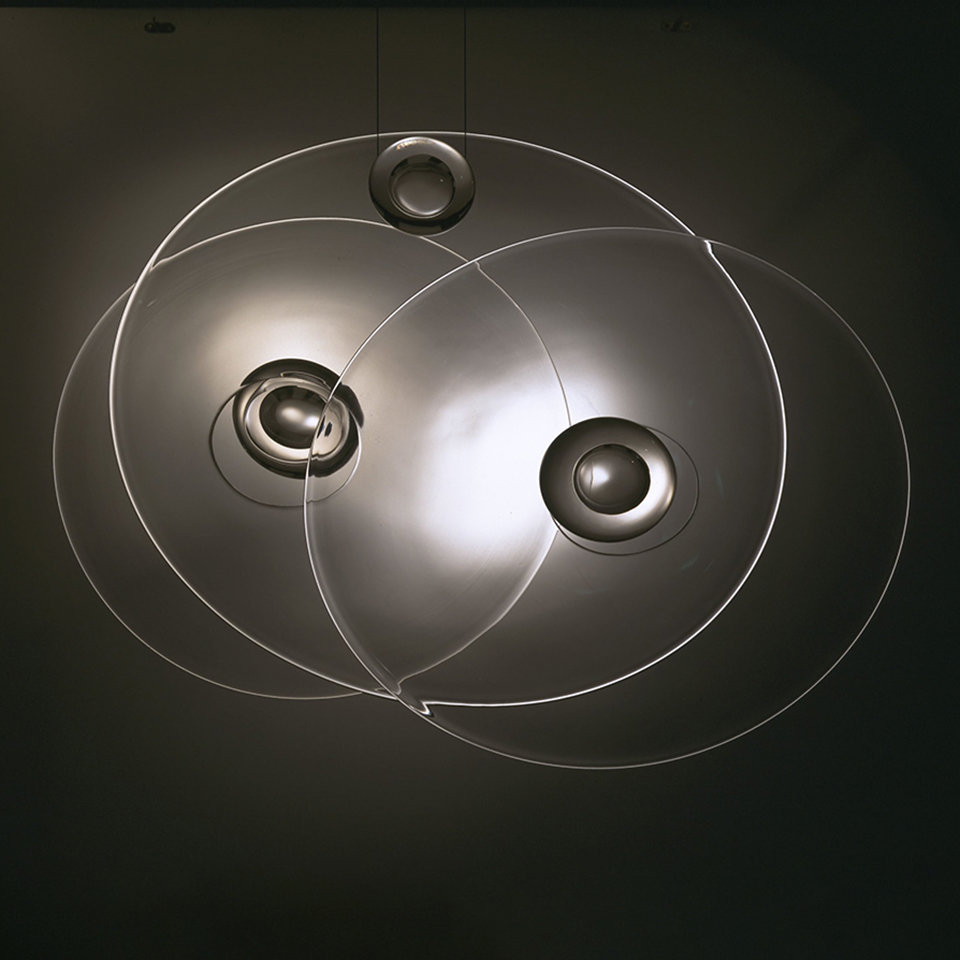

Born in Venice. Since childhood, Seguso was enamored by glass as a workable material and learned traditional Venetian glassmaking from his uncle, Alfredo Barbini, a glass master recognized internationally. Seguzo became a maestro glassblower at age 20. He studies glass sculpture and maximizes the beauty of transparent, colorless glass with the shape, space, and light working together in harmony. From the late 1970s, he developed his own style with fine circular and elliptical shapes. In the 1980s, he experimented with circular glass which he cut up into multiple pieces and reconstructed into a shape different from the original. Today, he combines glass with different materials such as metal, marble, and wood to create pieces that harmonize the beauty of transparent glass and express his inner poetic nature.

Dale Chihuly

1941~

Chihuly came across glass while studying interior design at the University of Washington. Fascinated by its possibilities, he went on to the University of Wisconsin in 1965 to study under Harvey K. Littleton, a founder of the studio glass movement. In 1968, he went to Murano, Venice to study at the Venini factory where Venetian glass traditions and the team approach to glassmaking made a strong impression. Armed with what he learned in Murano, he co-founded the Pilchuck Glass School, a glass art education facility in Washington state in 1971. As a place where glass artists from around the world can study and exchange information, the school continues to develop glassmaking. He has created a few series of glassware full of life and vitality including Macchia (1981–), Persian (1986–), and Venetian (1988–). They embody his incomparable artistic ideas, colors, and shapes. He has won many awards including the United States National Living Treasure award in 1992. In 1996, he was an invited artist at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Glass Artists held in Venice. In 2012 at the Seattle Center, he opened the Chihuly Garden and Glass exhibition facility where the garden resonates with his glass sculptures. He continues to be very active.

Modern Glass Museum

A novel contemporary glass art work that has been breathed new life into the 20th century.

Exhibiting works by Venetian glass sculptor Livio Seguso and American glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Discover the endless possibilities of glass.

Modern Glass Museum

A novel contemporary glass art work that has been breathed new life into the 20th century.

Exhibiting works by Venetian glass sculptor Livio Seguso and American glass artist Dale Chihuly.

Discover the endless possibilities of glass.

Artist introduction

Livio Seguso

1930~

Born in Venice. Since childhood, Seguso was enamored by glass as a workable material and learned traditional Venetian glassmaking from his uncle, Alfredo Barbini, a glass master recognized internationally. Seguzo became a maestro glassblower at age 20. He studies glass sculpture and maximizes the beauty of transparent, colorless glass with the shape, space, and light working together in harmony. From the late 1970s, he developed his own style with fine circular and elliptical shapes. In the 1980s, he experimented with circular glass which he cut up into multiple pieces and reconstructed into a shape different from the original. Today, he combines glass with different materials such as metal, marble, and wood to create pieces that harmonize the beauty of transparent glass and express his inner poetic nature.

Dale Chihuly

1941~

Chihuly came across glass while studying interior design at the University of Washington. Fascinated by its possibilities, he went on to the University of Wisconsin in 1965 to study under Harvey K. Littleton, a founder of the studio glass movement. In 1968, he went to Murano, Venice to study at the Venini factory where Venetian glass traditions and the team approach to glassmaking made a strong impression. Armed with what he learned in Murano, he co-founded the Pilchuck Glass School, a glass art education facility in Washington state in 1971. As a place where glass artists from around the world can study and exchange information, the school continues to develop glassmaking. He has created a few series of glassware full of life and vitality including Macchia (1981–), Persian (1986–), and Venetian (1988–). They embody his incomparable artistic ideas, colors, and shapes. He has won many awards including the United States National Living Treasure award in 1992. In 1996, he was an invited artist at the International Exhibition of Contemporary Glass Artists held in Venice. In 2012 at the Seattle Center, he opened the Chihuly Garden and Glass exhibition facility where the garden resonates with his glass sculptures. He continues to be very active.